Avery Singer in the studio. © Avery Singer. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth. Photo: Grant Delin.

by DAVID TRIGG

The world watched in horror as the terrorist outrages of 11 September 2001 unfolded in New York City. It was the worst attack on US soil since the 1941 bombing of Pearl Harbor, claiming the lives of nearly 3,000 people and impacting many more globally. Numerous artists have made work in response to that devastating day, notably Eric Fischl with his poignant Tumbling Woman (2002) and Miya Ando, who incorporated mangled steel from Ground Zero into After 9/11 (2010). Robert Gober’s series September 12 (2005-9) features pages from the New York Times superimposed with drawings of embracing couples. The work stopped Avery Singer (b1987, New York) in her tracks when she visited his 2014 MoMA retrospective. “I thought it was one of the most moving pieces of contemporary art I had ever seen,” says Singer, whose own experience of 9/11 has informed her ambitious solo exhibition Free Fall, at Hauser & Wirth London, which considers the power of memory and the impact of collective trauma.

“It was a sunny morning,” says Singer, who remembers that fateful day all too well. The artist, who had just turned 14, was living on Murray Street, a few blocks away from the World Trade Centre. She was home alone and getting ready for school. “I heard the first plane hit and I remember feeling very confused. It sounded like a plane was landing in my neighbourhood, but then the explosion felt like an earthquake. Suddenly, debris started falling all over the place and, from my front window, I saw the north tower in flames.” Not knowing what to do, Singer headed to school from where she was later evacuated. “Somehow, my parents found me and then we had to pick up my brother from his school further uptown. I didn’t know what was happening. Were we being attacked by a foreign country, or a terrorist group? It was just really unclear to me the magnitude of what was going on; then we heard that the Pentagon had been attacked and another plane had been hijacked. I didn’t know if there were a hundred planes out there ready to blow up New York City. I just went into survival mode and decided that I was going to do whatever I could to try to survive that day.”

Avery Singer: Free Fall, installation view, Hauser & Wirth London 10 October – 22 December 2023. © Avery Singer. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth. Photo: Alex Delfanne.

That night, Singer and her family slept in the projection booth at MoMA, where her father worked as a projectionist. “It was like a bunker,” she says. “But I felt way safer down there than being outside knowing that a plane could hit me.” The family stayed at various locations in the weeks that followed, eventually being allowed home the next month. “It was like being in a war zone,” she says, recalling that her street had been badly damaged by plane debris and the neighbourhood was cut in half by a large military fence. The gas was off and the phones were down, which added to the sense of abandonment. Worse still were the toxins in the air. “More people have died from getting sick than died in the event,” says Singer, whose father has since suffered from 9/11-related health problems.

The trauma of witnessing so much death and destruction that day took its toll on Singer, who has dealt with mental health problems and addiction issues. “The only way I got through the depression and post-traumatic stress disorder was falling in love with art,” she says. “I was in a terrible condition for years after. I honestly felt completely aimless, but art transformed my life. Art got me through some really dark places and still does to this day.” In 2008, she studied at the Städelschule, Frankfurt am Main, and, in 2010, received her BFA from Cooper Union in New York. Here, she worked with performance, video and sculpture, but it wasn’t until after she had left college that she started making the airbrushed paintings for which she became known, a shift that happened almost by accident.

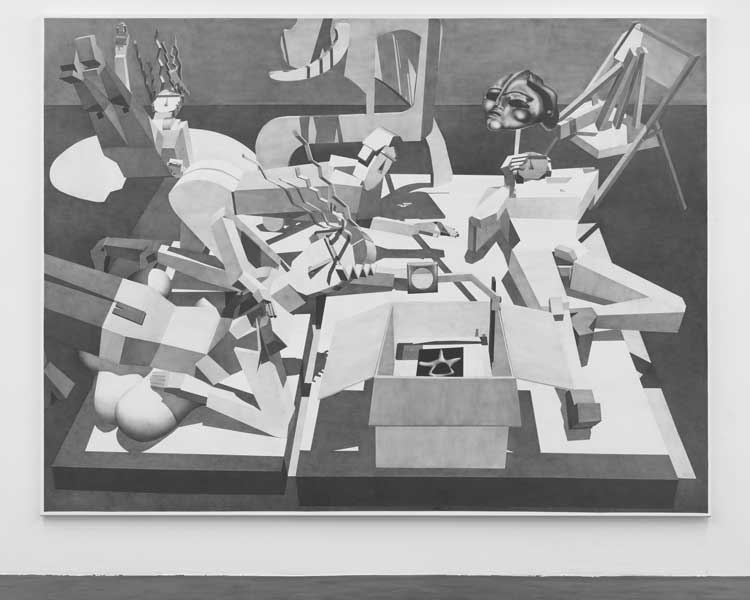

Avery Singer, The Studio Visit, 2012. Acrylic on canvas, 244 x 183 x 4.5 cm (96 1/16 x 72 1/16 x 1 12/16 in.) Courtesy: Kraupa-Tuskany Zeidler, Berlin. Photo: Roman März.

“I thought I would be a conceptual artist or have a performance-based practice, or maybe something involving video art,” she says. “Those were the kinds of things that interested me.” Having rented a studio in the Bronx, but with little money for materials, she began making drawings with leftover pencils and paper from her student days. The drawings were based on images created with the 3D modelling software SketchUp. “I had become acquainted with the program at Cooper Union because the architecture students there were using it,” she says. “I began making drawings of my models, but they weren’t very interesting. I had an airbrush in the studio and realised that this was a much more interesting way to create a drawing, the surfaces looked kind of like film grain.”

Working primarily in black and white, Singer at first sprayed her images on to Masonite before moving on to canvas and increasing the scale of her work. “It was then that I realised I’d become a painter, which was totally unexpected,” she says. This development is perhaps not so surprising considering that her parents were painters, and she grew up in a downtown Manhattan loft that doubled up as their studio. “I’m the product of a wild pack of bohemians, essentially,” she laughs. “I grew up in it, though I never in my life thought I’d be a painter.” Despite situating her work within the history of painting, her airbrush technique sets her apart from the majority of contemporary painters. Indeed, traditional brushes are anathema to Singer who, ironically, was named after the American painter Milton Avery. “They seem really cliched and irrelevant,” she says. “I honestly feel like a joke holding a paintbrush.”

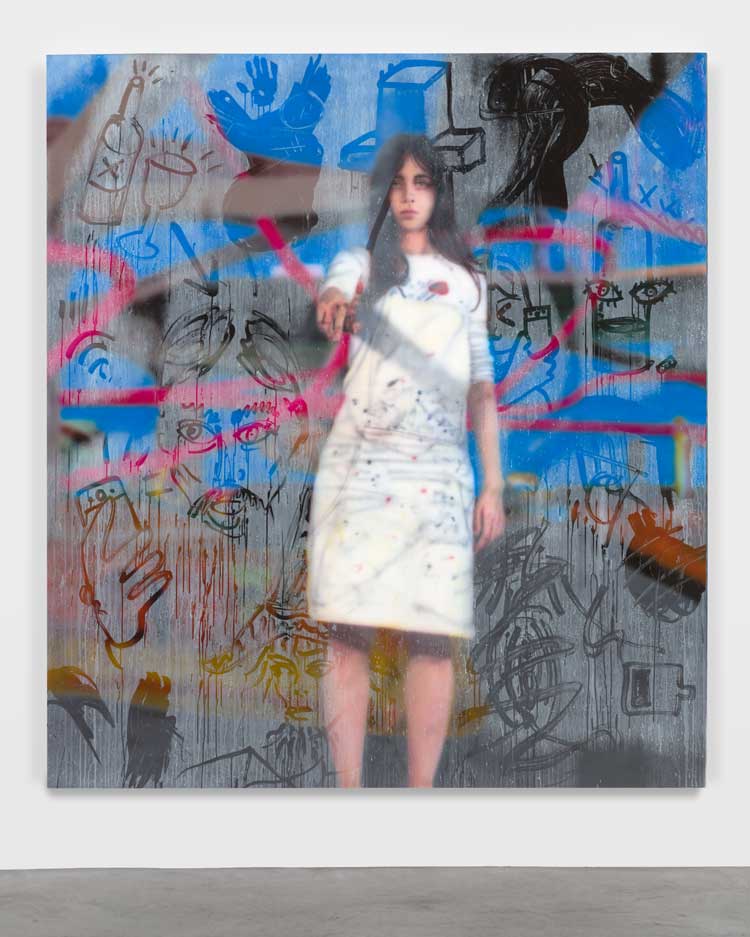

Avery Singer, Performance Artists, 2013. Acrylic on canvas stretched over wood panel, 198 x 264 x 4.5cm (78 x 104 x 1 3/4 in.) Ringier Collection, Switzerland. Photo: Jörg Lose.

Singer’s first airbrush paintings combine early 20th century art references, clunky 3D computer models and cinematic spaces. They collide elements from constructivism, cubism and geometric abstraction with fictional characters in a style reminiscent of early CGI (think the blocky graphics of Dire Straits’ groundbreaking video for their 1985 hit Money for Nothing). Each painting started life in the digital realm, designed in SketchUp or Photoshop, before being translated to the canvas using a laborious process of masking and unmasking. These grisaille works poke fun at art-world cliches, from life drawing classes and studio visits to esoteric performances and happenings. Dripping with fabricated nostalgia, they became vehicles by which Singer engaged the legacies of modernism while exploring complex plays of light and shadow and the relationship between digital and analogue media.

Taking her cue from contemporary artists such as Wade Guyton, who prints on to canvas with large-format Epson printers, and Laura Owens, who uses silkscreen, computer manipulation and digital printing in the creation of her paintings, Singer sought to incorporate a level of automation into her practice to negate evidence of her hand. She now uses a computer-controlled airbrushing machine – the Michelangelo ArtRobo – designed for large-scale industrial applications, such as applying branding to trucks, buses and aircraft. But the process is much more involved than simply clicking a button. “I’ve had a lot of struggles with this system,” she says. “It has to be tuned like a piano every time I use it; we have to do massive amounts of colour correction and it only works at a specific temperature and humidity, which is really difficult in the summer.” The process, which involves slowly building up images from dozens of layers, is also highly time-consuming. “It takes much longer to make one of these printer-based works than it did with the paintings I airbrushed by hand,” she says.

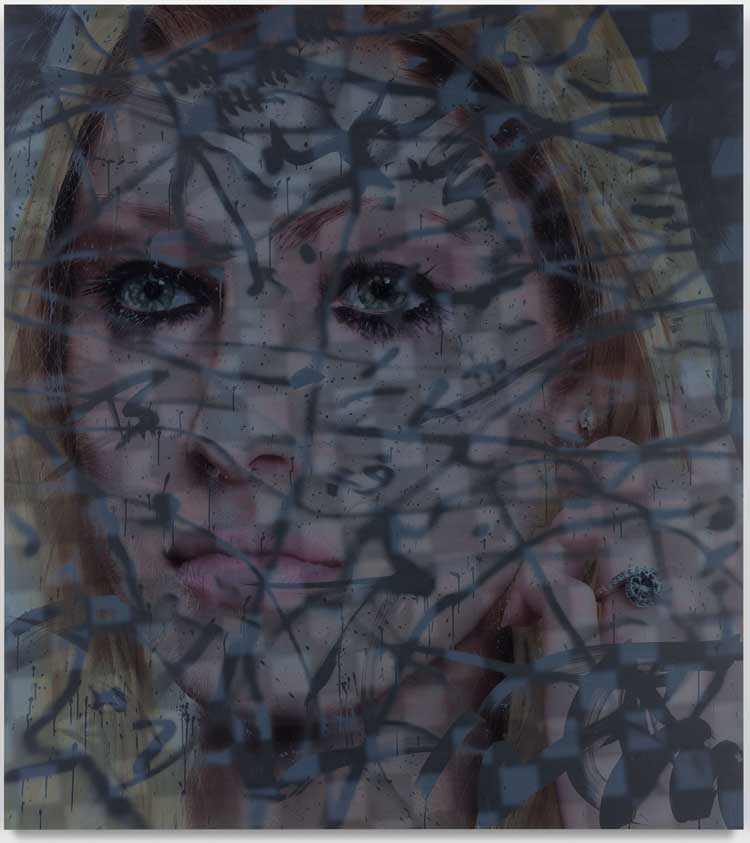

Avery Singer, Self-portrait (summer 2018), 2018. Acrylic on canvas stretched over wood panel, 241.9 x 216.5 x 5.1 cm (95 1/4 x 85 1/4 x 2 in). © Avery Singer. Courtesy the artist, Hauser & Wirth, Kraupa-Tuskany Zeidler, Berlin. Photo: Lance Brewer.

Although Singer’s process is largely mechanical, recent works have reintroduced physical mark-making through the use of rubber masking fluid, which she started exploring in about 2018. Take for example Self Portrait (Summer 2018), which began with a simple photograph taken in Singer’s studio. After airbrushing the image on to canvas, she doodled across the surface of the painting with masking fluid before spraying it with a fine mist of white paint. When the rubber dried and was peeled off, the result approximated condensation on a window, as if there were a steamy pane of glass covered in scribbles between the artist and the viewer. Now, gestural marks and scrawled imagery characterise the surfaces of Singer’s paintings, often partially negating the machine-painted imagery beneath, creating a push and pull of translucence verses opacity and a tension between presence and absence. “It’s meant to complicate what you’re looking at,” she explains. “Nothing about the application of the rubber seems related to the imagery at all. They’re really meant to be a foil to each other.”

Singer’s complex, multilayered technique seems apt for work dealing with traumatic memories, though it has taken several years of development to arrive at this point, and even longer for her to feel able to confront the past and deal with her experiences of 9/11 head on. “This is a really difficult subject for me. I didn’t feel comfortable touching it before because I hadn’t even shared my own story with most of the people I know,” she says. “It’s an aspect of my life that I’ve hidden for years, so making this work has taken me to a weird and vulnerable place.” Singer witnessed horrific scenes that day, from an injured man lying in the doorway of her school, to people falling to their deaths, and human body parts scattered across her neighbourhood – gruesome images that she says are “burnt into my memory”.

Avery Singer, unk-righthand.obj, 2023. Acrylic on canvas stretched over aluminium panel, 216.5 x 241.9 x 5.3 (85 1/4 x 95 1/4 x 2 1/8 in).

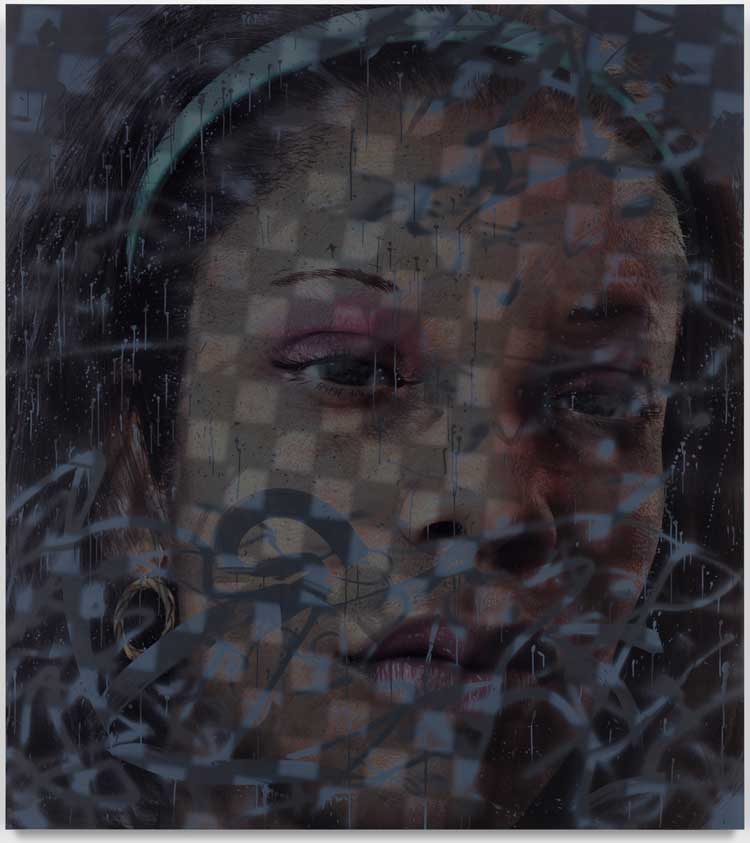

“A lot of the stuff that I saw is just really difficult and I don’t know if it’s even appropriate to show everything,” Singer says. “I have a painting of a dismembered hand, for instance, because that’s what my best friend found on her windowsill.” Other images in the show seem more innocuous: a local bus station, a cop car, a street scene and other half-remembered fragments. These are interspersed with large-scale paintings based on the people made famous by media coverage of 9/11, such as Marcy Borders, the 28-year-old Bank of America employee who became known as the “Dust Lady” after a photograph of her fleeing from the north tower covered in pulverised debris was beamed around the world. Another famous face is that of Rachel Uchitel, the grief-stricken woman seen clutching a photograph of her missing fiance, who had perished in the attacks.

Avery Singer, Deepfake Rachel, 2023. Acrylic on canvas stretched over aluminum panel, 216.5 x 241.9 x 5.3 cm (85 1/4 x 95 1/4 x 2 1/8 in). Photo: Lance Brewer.

“I allowed myself to be intuitively led by these media images and began to make computer models of them, to memorialise my own experience and create a monument for that moment in time,” says Singer, who has titled her portraits “deepfakes”. Each one is based on a digital composite comprising different photographs of the subject and, although they aren’t manipulated using AI, details have been added – makeup, jewellery, dust – that don’t appear in the source images. “I also took Renée Jeanne Falconetti’s acting from The Passion of Joan of Arc [1928] as an inspiration for the poses,” says Singer. Another digitally generated figure in the show is referred to as “art student”, a strung-out character smoking a crack pipe who, she says, is “an avatar that represents me dealing with addiction issues in the aftermath”.

Avery Singer, Deepfake Marcy, 2023. Acrylic on canvas stretched over aluminum panel, 216.5 x 241.9 x 5.3 (85 1/4 x 95 1/4 x 2 1/8 in).

The World Trade Centre played a significant role in Singer’s childhood and early adolescence. Not only did she grow up in the shadow of the twin towers, but they became a second home of sorts. “I spent a lot of time there because my mom worked in the towers as a secretary until 1999,” she says. “I remember going there to see her and we would go up to the observation deck and get pizza in the basement or whatever.” The complex wasn’t just a place to hang out with her mother, Singer also met friends there. “My two best friends lived a block or two away. I was on the north side and one friend was on the east side and the other was on the west side. We spent a lot of time there and I have a lot of fun childhood memories in that area.” The Borders bookstore in Building 5 became another important destination. “There was a public library in my apartment building, but it was like a homeless shelter with passed-out drug addicts in it, so I never wanted to spend time there. I would pretend Borders was a library and just sit there for hours reading books,” she recalls.

Avery Singer: Free Fall, installation view, Hauser & Wirth London 10 October – 22 December 2023. © Avery Singer. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth. Photo: Alex Delfanne.

For Free Fall, Singer has replicated her memories of the World Trade Centre buildings, transforming Hauser & Wirth’s London gallery into an architectural environment that highlights the contrast between the twin towers’ iconic design by Minoru Yamasaki and mundanities of office life. “The architecture was so magnificent from the outside, but inside was like a banal centre of finance and trade capital with terrible corporate decor,” she says.

Avery Singer: Free Fall, installation view, Hauser & Wirth London 10 October – 22 December 2023. © Avery Singer. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth. Photo: Alex Delfanne.

Part stage-set, part minimalist sculpture, Singer’s scenography takes visitors on a gently disorienting journey, from banks of elevators and anonymous corridors to bland office furniture and Yamasaki’s famous 18in slit windows, designed to prevent workers from experiencing vertigo. “Architecture is really important when you make an exhibition,” says Singer. “The white cube is a space that you really need to define architecturally. I experimented with this a bit for my show at the Institute of Contemporary Art in Miami, but realised that I didn’t push it far enough. For London, I wanted to go maximalist and use the Trade Centre architecture as a way of framing my work.” Singer has even created a bookstore piled high with books published before 2001. “It’s one moment where I’ve tried to inject a little bit of humour; the nice Hauser & Wirth bookstore replaced by crappy self-help books from the late 1990s.”

.jpg)

Avery Singer: Unity Bachelor, installation view, Institute of Contemporary Art, Miami. 22 April – 15 October 2023. Photo: Zachary Balber.

The installation additionally features shredded paper scattered on the floor, recalling the piles of trading slips that regularly littered the New York Stock Exchange in the pre-digital era. “It’s a symbol of American capitalism,” say Singer, who concedes that the fragments also recall the clouds of scraps that cascaded from the twin towers on 9/11. Of course, it was not just paper that fell from the towers before they collapsed that day, a gruesome truth alluded to by the exhibition’s title. “I began to title a lot of my paintings Free Fall,” says Singer. “In this context you’re thinking about falling people, but it also relates to my experience of dealing with extreme trauma and loss, where I felt like I was in free fall, mentally, emotionally and spiritually.”

Avery Singer: Free Fall, installation view, Hauser & Wirth London 10 October – 22 December 2023. © Avery Singer. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth. Photo: Alex Delfanne.

Singer describes the exhibition as “an emotional landscape”, one in which viewers are invited to enter and “define their own experience”. In this, the show is generous, acknowledging that 9/11 affected all who witnessed it, whether first hand or mediated through mass media. Yet it is also a highly personal and autobiographical reflection on a moment of terror and survival. When Singer’s childhood friends learned of the project, they wanted to know if making the work had been a cathartic experience. “I had never thought about that,” she says. “Nothing about what I make is cathartic, it’s more like anti-catharsis! It just feels like material to me, though I think the best story an artist has to tell is the one of their own life.”

Avery Singer: Free Fall is at Hauser & Wirth London, from 10 October until 22 December 2023.

Avery Singer: Unity Bachelor is at the Institute of Contemporary Art Miami until 15 October 2023.